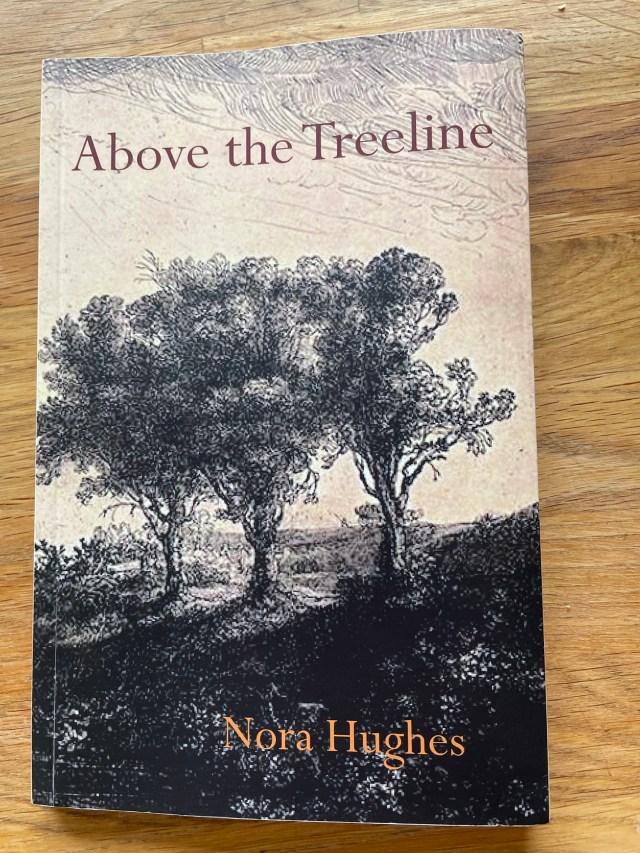

Spot on review of Nora Hughes’ poetryAbove the Treeline by Chris Beckett in londongrip.org.

https://londongrip.co.uk/2026/01/london-grip-poetry-review-nora-hughes/

Thanks to Chris Beckett for such a sensitive review which highlights the “emotional legacy” of Nora’s life in Belfast and how “wherever the poet goes, her Belfast girlhood and its landscape remain at her side, sometimes as a loneliness, a ‘hunger in the heart’ from the Irish word Cumha (in a beautiful poem of the same name) “